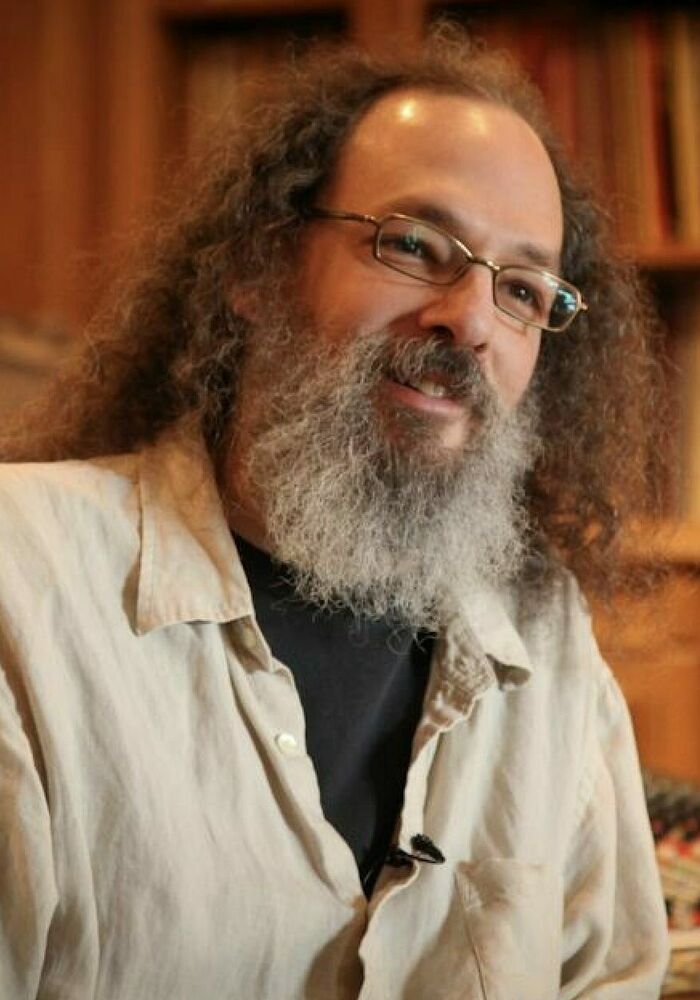

Grammy-winning producer and mixer Andrew Scheps has spoken to Headliner about his incredible career to date, from the lessons he learned working on Michael Jackson’s HIStory album as a budding studio talent, his work on new Fellow Robot album Misanthropoid, and his ongoing relationship with plugin specialist Waves.

For almost three decades, Scheps has been working with some of the biggest and most iconic names in music. To date he has received three Grammy Awards for his work with Adele, Red Hot Chilli Peppers, and Ziggy Marley, notched up over 20 further nominations, and worked with the likes of Green Day, Metallica, Hozier, Johnny Cash, Michael Jackson, and many others.

Among his most recent projects was a collaboration with California’s Fellow Robot, co-producing and mixing the band’s latest record Misanthropoid. Completed over a two-year period, the album is a concept record of sorts. Indeed, the band itself could be described as a concept project, having formed as an extension of singer Anthony Pedroza’s The Robot’s Guide To Music sci-fi novel, with that source material providing the basis for much of the band’s lyrics. As such, Misanthropoid is a record that seeks to explore what it means to be a human being.

To find out more about the record, Headliner sat down with Scheps to discuss his working process with the band, as well as some of the most pivotal moments in his career and how he arrived at where he is today…

How did you first get to know Fellow Robot? Were you aware of the origins of the band before you started working with them?

It's a pretty typical story. They sent a song to my manager in LA who then forwarded it to me. They sent him a song from their previous release, and I really liked it. We exchanged emails, I mixed the song, we finished it up and it was all great. I think it was all done by email at that point, and I wasn’t aware of the history of the band. So when they started working on the next record they got in touch and said they’d like to work with me more. This was pre-Covid, so we were talking about possibly recording in Monnow Valley in Wales. That’s where I would record and produce most of the time. But of course that all went south and they just kept working on their record. They would send me demos and rough mixes. We went back and forth on the songs six or seven times and then it was time for me to mix. But it was a very organic process.

How collaborative was your relationship with the band?

They are really talented and have a great vision of the finished product. There were a couple of songs where we went back and forth on the groove and the rhythmic way the song would be presented, but for the most part that stuff was pretty solid by the time I heard it. And then it was about arrangement and how to highlight certain things. When you are the band and you are writing and demoing, you know how everything goes and maybe you don’t step back far enough to notice some of the rough edges that occur as you go between things. So it was a lot of details and overarching stuff, and they were open to absolutely everything, which was fantastic.