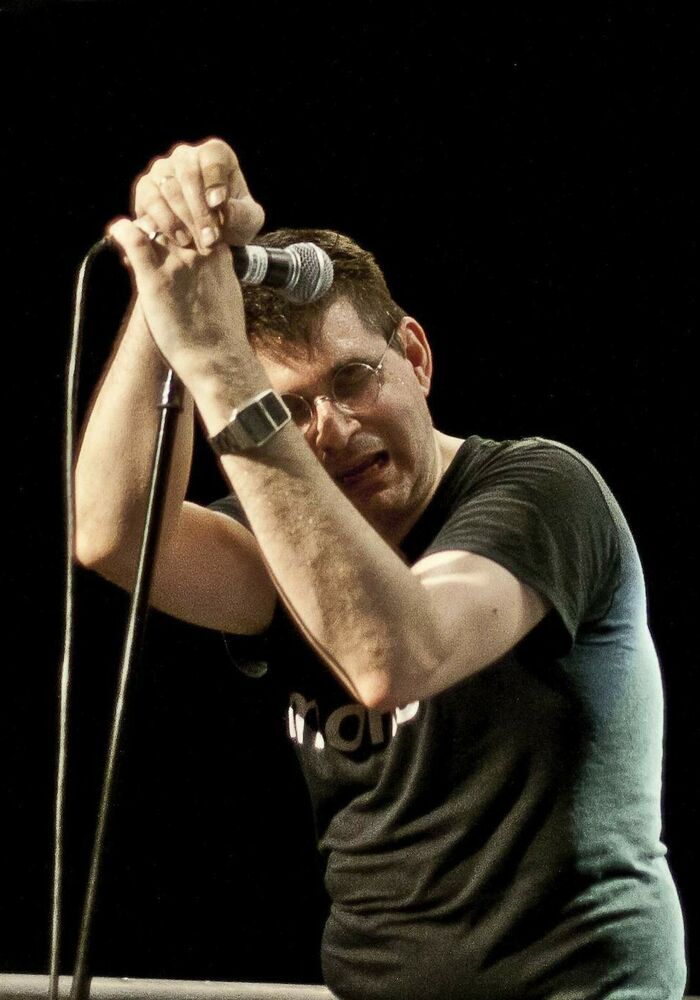

On Wednesday May 8, Steve Albini, one of indie and alternative rock’s most revered and beloved engineers and musicians, died after suffering a heart attack. He was 61 years old. Just a few short weeks before his passing, in what we believe to be his final interview, Albini joined Headliner for an in-depth chat about the 15th anniversary of Manic Street Preachers Journal For Plague Lovers record, as well as the role he played in, as he puts it, “changing the paradigm” of the music business. Here, his customary wit, humility, and boundless knowledge flows freely as ever, as he reflects on an album that remains a genuine outlier in both the Manics’ catalogue and his own towering body of work.

It’s a bright, Spring afternoon in London when the face of Steve Albini materialises on the laptop screen before us. Sporting a grey beanie hat, a pair of round, dark-rimmed glasses, and his trademark navy blue overalls, he cuts an unmistakable figure. Typically, when interviewing Albini via video call, he can be found in the control room of his Chicago studio, Electrical Audio. Today, he informs us, he’s in the “business office” of the facility. It’s a non-descript room, save for a landline telephone beside him that he answers once or twice during our conversation, seemingly fielding calls and inquiries about studio bookings. It’s impossible to imagine other producers - a term he famously rejects – of his standing in the rock world adopting such a workman-like approach. When phoning the studio, he’d be the one to pick up. When emailing its generic contact email address, it’d typically be Albini responding. Though strange in and of itself, it’s all rather typical of the man himself.

In almost every way, our final conversation bears every standard Albini hallmark. As expected from a man who refused a production credit and royalty payments for his work on one of the most critically and commercially successful records of the ‘90s with the biggest rock band on the planet, he is keen as ever not just to downplay but extinguish any plaudits thrown his way when discussing his role on any given record.

Unexpected, however, is the realisation just a few weeks later that our interview may well be the last he ever gave. In a career spanning over four decades, the impact he had on the lives of those he worked with was indelible. As indeed it was for those who adored the records he conjured into being. For all of his modesty – “if you listen to the records I’m best known for and think that I’ve done a good job, what you’re hearing is what the band did. I’m not in there playing or making that music. I’m making a recording that allows you to hear that as it was,” he once told Headliner – his masterful ability to extract the purest essence of a band and preserve it in its most pristine form is unrivalled. From alt rock giants like Nirvana, Pixies, The Breeders, PJ Harvey, Bush, and the Manics, through to the hundreds of underground punk rock bands he worked with through the years, including his own bands Shellac and Big Black, his oeuvre is not only peerless but testament to his lifelong passion for capturing bands at the peak of their powers.

It is for all of the above that the Manics saw fit to approach Albini to work on an album that would prove to be one of the most highly anticipated records of their career. Released in 2009, Journal For Plague Lovers was constructed around a boxful of unused lyrics left behind by the band’s former chief lyricist and figurehead Richey Edwards, who disappeared shortly after the release of their incendiary third album The Holy Bible (1994). Having vanished on the eve of a promo tour to the US in February 1995, Edwards has not been seen since, and on November 23, 2008, was officially “presumed dead” by police.