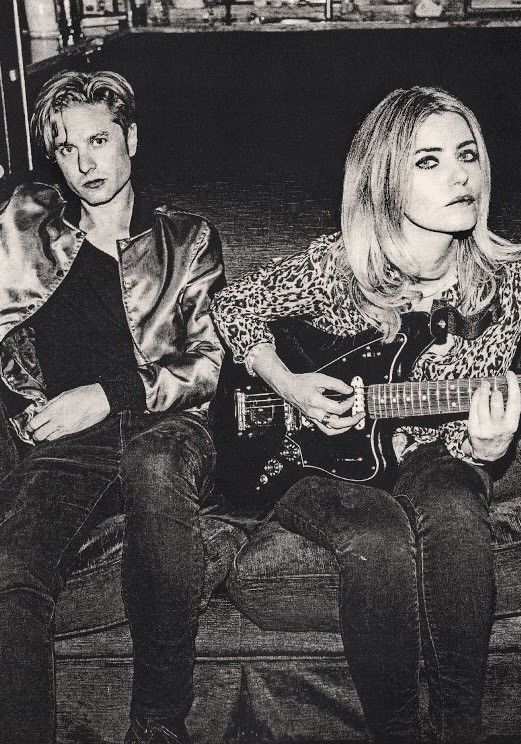

For the first time in nearly 15 years, Blood Red Shoes are missing out on their usual romp of the UK festival circuit. We recently caught up with the alternative rock duo from Brighton to learn about how they’re staying creative, what they’re missing at the moment, and the tours that pushed them to breaking point.

Blood Red Shoes were extremely lucky to have finished recording in the studio just two days before lockdown struck in the UK back in March. Since then, the pair have been focusing their creative efforts on writing, “and having discussions about artwork and aesthetics and all the other things that go around an album,” explains Steven Ansell, who makes up one half of Blood Red Shoes.

The pandemic has given the pair a lot of time to think about the non- musical side of things, combining all the elements to portray and contextualise their music in an artistic and expressive way.

“The whole universe going on pause for a while has given us more time to think about that than ever before,” adds Ansell.

“So it’s been quite positive in a way - It’s given us the option of doing something we don’t typically spend a lot of time on. I think using your creative energies is sort of like whack-a-mole: you smash it down in one place, and it will pop up somewhere else.”

Usually at this time of year, the band would be gracing the stages of festivals everywhere with their bold punk rock sound, something they have been doing religiously every summer since 2007.

“Obviously we can’t play which is really hard, but once you kind of accept that, I think you have to then find other ways to fulfil your creative energy,” says Laura-Mary Carter, the second half of the duo. “I definitely miss it, but I just kind of feel like summer didn’t really happen - we’re living in a bit of a limbo right now but then everyone’s in the same boat.”

In 2014 the band formed their own label Jazz Life, a decision that came about through feelings of disillusionment for the music industry. I asked the pair for their thoughts on the democratisation of music and the digitalisation of the industry in terms of putting control back into the hands of artists.

“After a while you realise that no one really cares as much as you do,” Ansell responds. “They take the thing that you’ve invested your heart and soul into and stick it on a big list of things for them to do. You’re not really looked after, and for that privilege they take 80% of the money. So us and a huge amount of other artists are now questioning this trade-off and asking what exactly are we getting out of it?

“Unless you’re in some sort of top tier, you get very little back for giving away the rights and ownership of your entire craft. Increasingly everybody’s realising this and because it’s easier now to distribute your stuff digitally, artists can take a huge chunk back with regards to the control of their own income and decision making.”

The origins of Get Tragic – the band’s fifth studio album which they released in January 2019 – go back to when they were gigging relentlessly over a period of around six years, during which they almost exhausted themselves beyond repair. “If I think about it now, the period from about 2007 or 2008 to 2014 is like one very blurry blob,” Ansell recalls.

“From 2007 onwards when we signed up record deals and got management and booking agents and started doing festivals, we threw everything we had into the band. It basically just kept expanding from there.