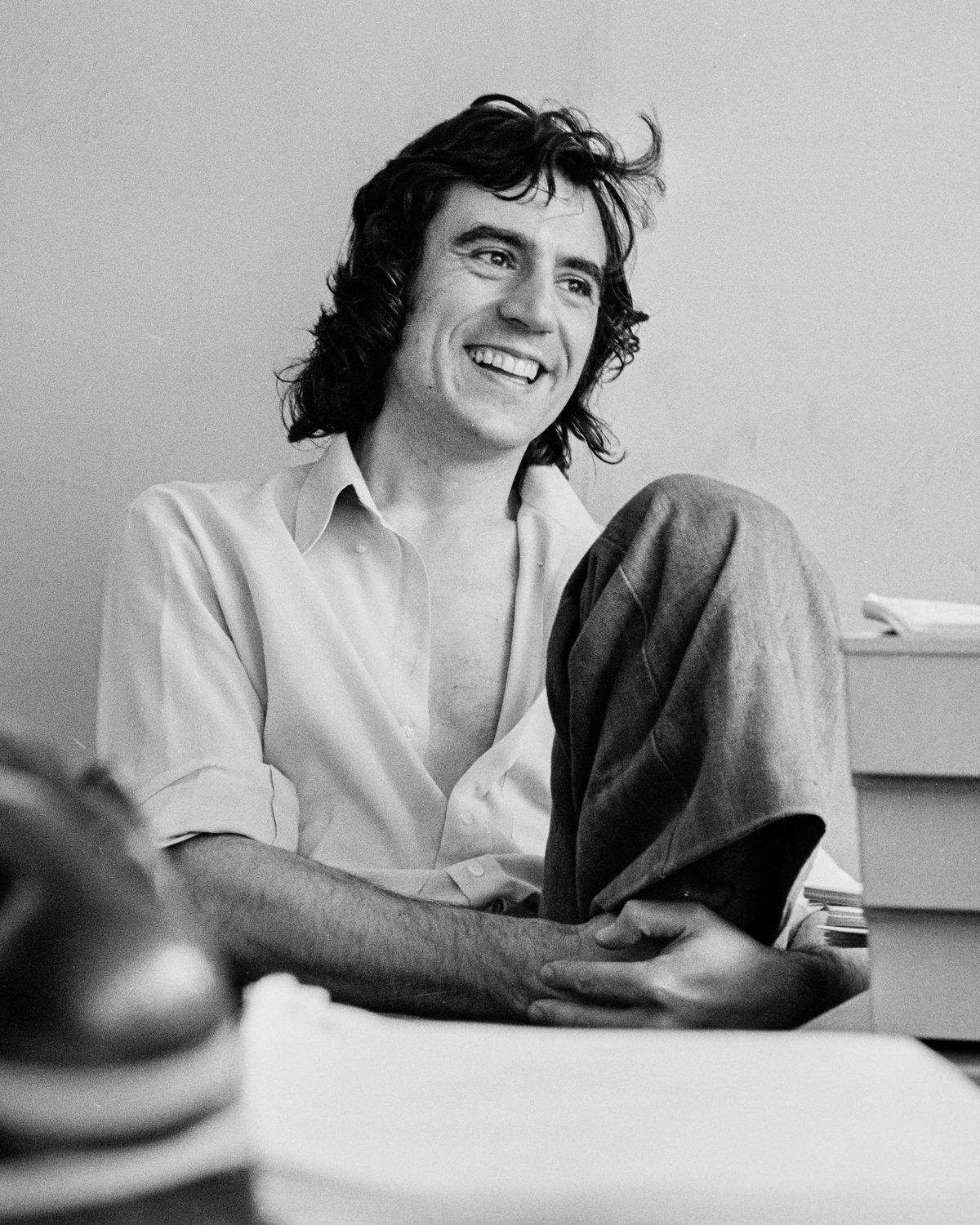

Chances are if you’re asked to name a Monty Python song, you’ll land on one co-written by André Jacquemin. The honorary Python gives a glimpse into what it was like to join the flying circus 50 years ago, and why he’s been working with the legendary comedy troupe ever since.

The first time André Jacquemin met the Pythons (John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Michael Palin, Eric Idle, Terry Jones and Graham Chapman), he had no idea who they were. At 18, he was working as an engineer at a London recording studio when he was asked to man the desk while the receptionist was at lunch.

“I wasn't watching TV at the time because I was too busy recording and earning a living as an engineer, so I wasn't familiar with Monty Python at that time,” he admits.

“This guy came up and said he wanted to do a voiceover for a friend of his for a showreel, and asked if that was the sort of thing we did here. I said ‘Yes, we can do that sir, no problem at all’. I looked in the diary, and there were two engineers (me being one of them), and the other was Alan Bailey. On the date he picked, Alan was busy, so I ended up doing it.”

Over the course of the next year, the various Pythons would come in to record parts for a voiceover reel, which Jacquemin found odd, as he couldn’t work out why it was taking them so long. It turns out they were working around Palin’s busy filming schedule. Impressed with Jacquemin’s work, he was asked to work on an album they were putting together (Monty Python’s Flying Circus), which is when he finally got to meet the entire Python ensemble.

“I thought to myself at the time, ‘why would anybody want to make a talking record?’ That seemed a bit strange. So I went down to Mike's [Palin] place, and everybody was in the room apart from John Cleese. I was introduced to Eric, Terry Jones, Terry Gilliam and Graham, and then in walks John Cleese and the penny dropped about who they all were.

"The others were not as high profile as John at the time; he was the one that was used in any promotional pictures. It was a surprise when I found out who they were, especially after having worked with Mike for nearly a year!”