On October 27, OMD (Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark) release their 13th album Bauhaus Staircase. Headliner joins singer and bassist Andy McCluskey to find out about how the brand embraced new ways of working for the very first time, the trials and tribulations they have endured down the years, and why this could well be the band’s farewell record…

For a band that formed and played their first gig as a dare, OMD aren’t doing too badly. Forty-five years into their career, they have just released their 13th studio album – a typically sonically expansive affair called Bauhaus Staircase – and have announced their biggest headline show in London to date, as they take on The O2 arena on March 24, 2024. Since their return to making music together over a decade ago, their recent output has garnered rave reviews, with their previous album, 2017’s The Punishment of Luxury, helping introduce the band to new, younger audiences while expanding upon, rather than straying from, the blueprint that has made OMD one of the most influential bands of their generation.

“It’s amazing to us that we’re still doing it,” McCluskey says with genuine incredulity as we chat via Zoom. “OMD only got together to do one gig. It was a dare. It happened by accident!”

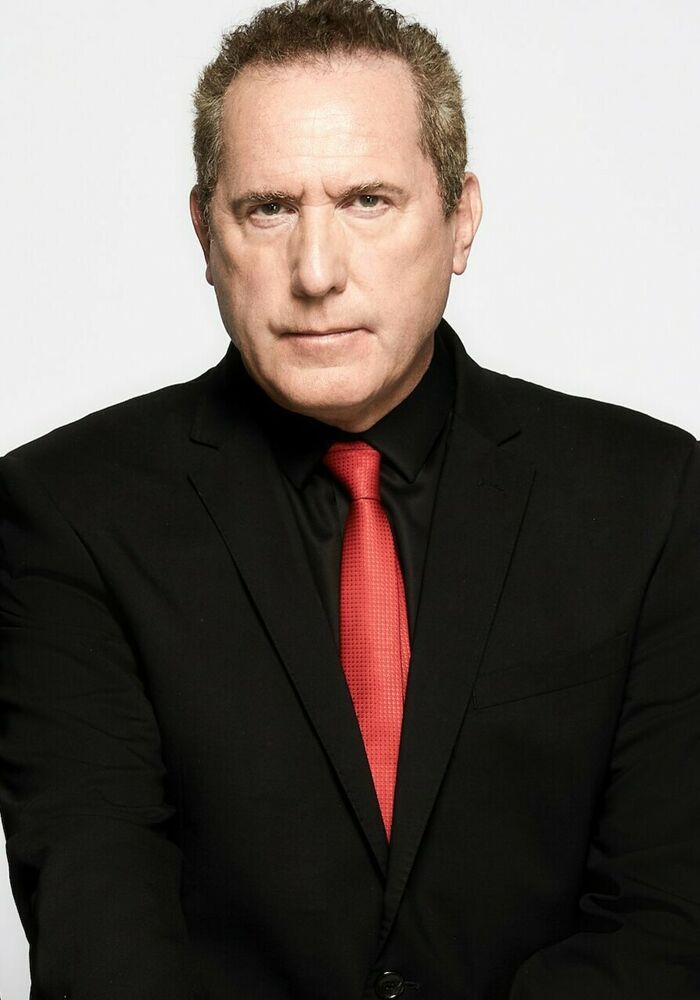

Joining us from “a lovely hotel in central London”, McCluskey is an endearing figure. He’s frequently funny with an affable, down to earth manner that feels immediately familiar. The icy mystique that tends to cloak OMD and their 1980s electro pop contemporaries, such as Depeche Mode, Pet Shop Boys, and their beloved Kraftwerk, evaporates in conversation.

“Paul [Humphreys] and I have known each other since we were seven,” he continues, picking up the story of how OMD came into being. “His friends had a band, and they knew I had a bass that I got for my 16th birthday. So, he’d seen me with my new bass and he came round with his mates as they needed a bass player. But because we lived so close we ended up becoming musical buddies, and I would take my German imports round to his house. He’d made himself a stereo because he was a whizz at electronics. That’s where the symbiotic relationship started – he had the stereo, I had the records. And then we just had this mad idea of trying to make music.

“I had my upside-down bass guitar, because the only one I could afford was a left-handed one and I’m right-handed, and I still play upside down to this day. And Paul started cannibalising his auntie’s radios for circuits to make things. But even when we got a cheap Vox organ and electric piano the music we were making was still pretty weird and ambient, and our mates who were into Genesis and the Eagles and Pink Floyd, thought we were shit! But in the summer of ’78 we discovered that there were other people interested in electronic music. We heard the Human League and The Normal and we just knocked on the door at [Liverpool venue] Eric’s and asked if we could play. He said, ‘yes, what are you called?’ We didn’t have a name because we thought he’d tell us to bugger off!