James Murphy’s story almost flies in opposition to the other characters, in that he is older than a lot of those breaking through and is almost at the point of giving up on music. Yet he takes off in a huge way with LCD Soundsystem after the initial buzz around the rest of the scene has peaked. What were your observations of his place in this story, and how did it feel to document the birth of LCD Soundsystem having so comprehensively documented [what we thought was] its farewell with Shut Up And Play The Hits?

Will: James’s story was happening at the same time but is very different for sure. He was trying to figure out what he was going to do and that’s what we really liked. There are two stories running alongside each other.

Dylan: There is an almost accidental nature to it. The Strokes arrive as this fully formed band and that’s all they have in their sights; Karen has this urge to perform; Interpol are workmanlike; and James just gets there through a series of failures in one thing or coming up in opposition against others. He creates in opposition to people. When David Holmes comes on the scene, he’s like, ‘this guy doesn’t know how to play instruments, I can do what he does’. We really liked his story as a story, because as hard as he is to work with for some people and single-minded as he can be, he is almost the underdog of the story. He is 10-15 years older than some of the other people in the story, and then suddenly he’s the last man standing when you look at popularity now.

In terms of revisiting LCD and doing the origins story, that was one thing at the beginning we were worried about, as we didn’t want to be treading the same ground. But Shut Up And Play The Hits is a concert film, and it’s a single moment. It’s not telling a protracted story of the band, other than James’s decision to end it. We saw it as a midlife crisis in reverse. Most people hit 40 and decide to start a band, he hit 40 and decided to end his. There was something psychologically interesting in that. But his story is one of the strongest parts of this film. And James recognised the changes in technology and the changes in how people consume music very early.

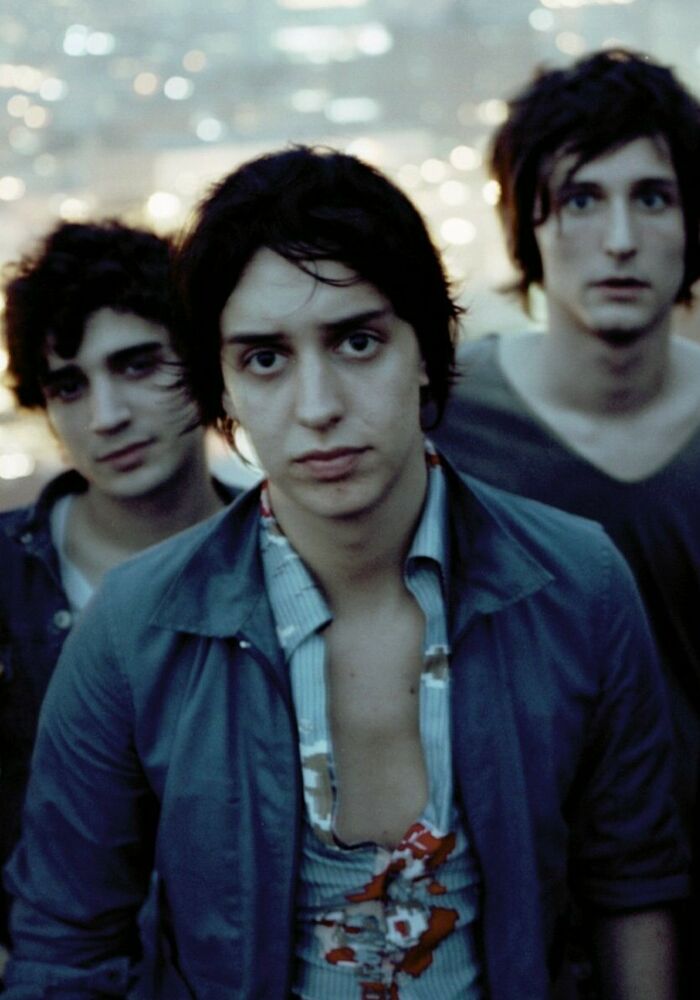

How do Interpol slot into the story for you? They are clearly a staple of the scene but they also feel somewhat at odds with the more obvious rock’n’roll aesthetic of Yeah Yeah Yeahs and The Strokes, and the influences feel more British than NYC

Will: In a different way they were the underdogs of the guitar scene. They had a clear vision of what they wanted to do, and while everyone else was exploding they were a year or two behind but just carried on and did it.

Dylan: Very tortoise and the hare. They really worked at being a band, crafting the songs and doing the steps you had to do at that point. They just hit differently. The sound and aesthetic was completely different. And England also played an integral part in their development, in terms of the press getting behind them and putting them in with that scene. When you have journalists putting their name alongside The Strokes and the others, then they almost become a de facto part of the scene despite being so different.

Are you surprised at how many of the bands featured are still going strong 20 years later?

Will: Having got to know their characters a bit I’m not surprised. They are all creative forces and have all reinvented themselves as they’ve gone along. Usually, a scene finishes and that’s it, but I think it’s exciting that they are still making stuff.

Do you have any personal favourite records from that time?

Dylan: The first Strokes album still stands up. It’s probably one of the greatest debut albums ever.

Will: The first Yeah Yeah Yeahs album as well. It’s still an amazing record. They all are really. Going back to listen to all of that music again and hearing live versions we hadn’t heard before was really exciting.

Any thoughts on what your next project might be?

Dylan: If we do another music documentary it would have to take a different form. With the Blur documentary, that was a traditional story of a band, although we interweaved it with the story of their reunion and Graham and Damon becoming friends again. Shut Up And Play The Hits was a concert film, so if we did a another one we’d have to reinvent the form of it. And it would have to be the right story. We’re looking at other things for now, but never say never.