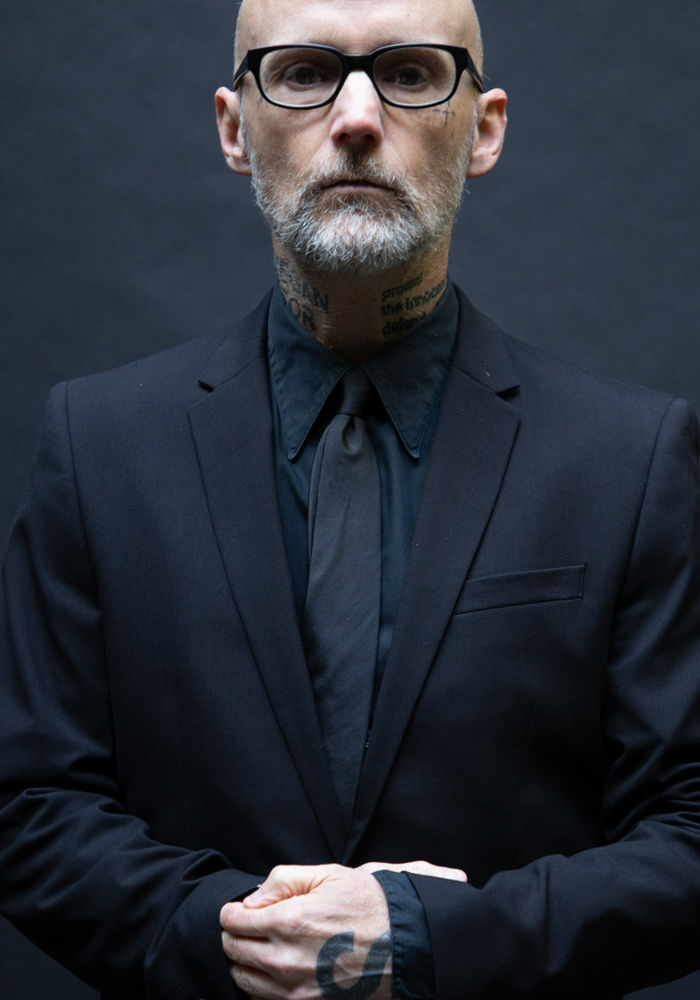

There is very little Moby has left to put on a bucket list — he’s won the awards, played to audiences as far as the eye can see, collaborated with his hero and idol David Bowie, and lived the rockstar lifestyle as much as one can without a fatal ending. Not to mention he is widely regarded as one of the most important and pivotal figures in dance and electronic music since music ceased to be purely acoustic. And yet, Moby has been very keen to let as many people as he can know that all that fame and success left him feeling empty (he goes as far as to say he’d pack it all in to spend more time on his animal rights activism), as seen in his brilliant new film, Moby Doc, and in this retrospective time where he releases his orchestral greatest hits album, Reprise.

Moby Doc, which was released in May 2021, is about as original, creative, funny yet sardonic a music documentary you could hope to see. It’s unconventional because it seeks to tell the fascinating story of Richard Hall and his road to becoming Moby and the eventual all-engulfing success.

But there’s no hint of self-congratulation or pats on the back: his traumatic childhood is wryly shown via quirky animations, and he narrates how his spiralling success and fame went hand in hand with increasing addiction issues and heavy depression.

We see him living in an abandoned factory with no bathroom or running water, but just enough electricity to make music on his basic equipment, which he describes as one of the happiest times of his life. Yet, when his breakthrough single Go sees him performing and appearing around the world, the fame lifestyle did damagingly seduce him.

As the film gets more existential and we see Moby stood atop a mountain (to show what tiny lifeforms we really are), lauded filmmaker David Lynch fittingly turns up to discuss what life really means.

Headliner kicks off our conversation by remarking that May 28 of this year must have been a pretty special date for Moby, as it saw both the release of Moby Doc, and his latest album, Reprise.

“I did go out to dinner with a few friends who had also worked on the movie,” he says.

“You would think, rationally, that releasing a big orchestral album and releasing a movie would be a day of joyful celebration. Of course, I was happy to be releasing both things. But I just kept working on new things. It's almost a compulsion. I feel like I should be dealing with that in therapy, the compulsion to work seven days a week. Friends have called me a workahoIic, but I think that I have more enthusiasm for work than for anything else.”

If you watch the film, you’ll undoubtedly agree that Moby being a bit of a workaholic these days is definitely a best-case scenario. After Go sees him become the biggest name in electronic music, Moby Doc charts his failed punk rock album Animal Rights, leading to the dizzying heights of his landmark record Play in 1999.

Its success was largely down to the song Porcelain, surely still one of the most beautiful downtempo songs ever released, and likely to have been heard by virtually every set of ears on the planet at this point.

With that being said, this period was the absolute height of Moby being completely and utterly lost in the bubble of fame and partying every single night, in which he would very rarely go to bed before 7am.

Hence why the film makes sure to cleverly downplay his huge material success by setting it against shots of nature’s overwhelming power and beauty, and the incomprehensible vastness of outer space.